Dementia in Our Mob and around the world

What is Dementia?

Dementia is a medical term which describes a collection of symptoms including memory loss or affects on the brain that lead to problems for people in everyday activities and independent living. Dementia can also be linked with changes in personality, mood and behaviour. There are many different causes of dementia, which have an impact on the types of changes a person experiences and the way dementia progresses over time. Some common types of dementia are described below. Many older people experience more than one type of dementia, which can be referred to as mixed dementia.

Dementia and our Genes

Many people have a family history of dementia, but this does not necessarily mean they will also develop dementia. Some types of dementia are caused by changes in genes passed from parent to child, but these are very rare and usually have a relatively young age of onset (i.e., 40s or 50s). Examples include familial Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and some types of fronto-temporal dementia. The most common form of dementia is late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, which usually occurs later in life and becomes more common at older ages. This is the case in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, as well as in most populations worldwide. The causes of Alzheimer’s disease in late-life are not yet fully understood, but probably include both genetic and environmental factors. People with certain forms of a gene called APOE have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (while other forms have a lower risk). However, even people with this genetic risk factor can live to very old ages without developing dementia. There has been very little research on the role of genetic factors in dementia with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

For more information, see: https://www.dementia.org.au/information/genetics-of-dementia

Dementia Research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians

Understanding dementia

In Queensland, a study about how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people understood dementia showed there are some important knowledge gaps around dementia in the community.

These gaps include knowing how long people live for after being diagnosed with dementia and some of the risk factors that impact on getting dementia in later life[1, 2].

It was also revealed that there are some common misconceptions about Alzheimer’s disease and how to look after someone with dementia, with younger people most likely to have little or no knowledge at all about Alzheimer’s disease[2].

Most of the people who took the survey defined Alzheimer’s disease as either ‘memory loss’ or ‘forgetfulness', but only a few mentioned that the disease affected the brain or got worse over time. Even fewer talked about Alzheimer’s disease and dementia being something related to older age[2].

Some research suggests that there are understandings of dementia involving religious or spiritual meanings. This may mean looking for care that includes traditional healers or religious or spiritual approaches to dementia[3].

Dementia statistics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

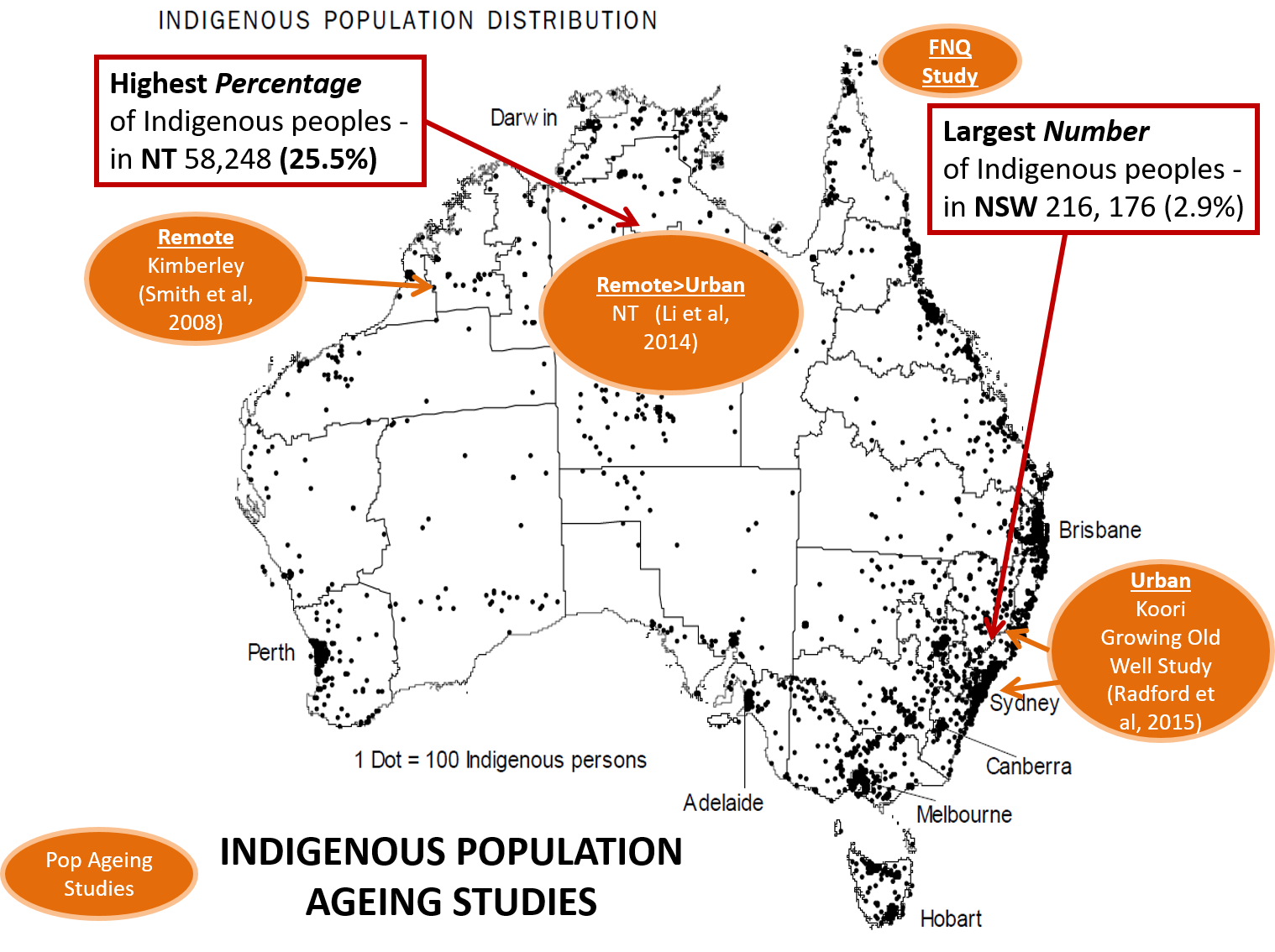

A 2014 study in the Northern Territory (NT)[4] explored dementia prevalence using information gathered through primary care sites, hospital admissions, aged care services and death records. The estimated prevalence of dementia (that is, the part of the population with dementia compared to the part without, as a percent) for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population aged 45 years and older was 3.7%, compared to 1.1% for non-Indigenous people in the NT.

How dementia is measured also matters for how often it is found in a community. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, Western medicine tests for dementia may not pick up on the ways Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience and describe their health worries, which can lead to the wrong diagnosis.

Studies of dementia prevalence in the Kimberley region of Western Australia that used a specific type of measure adapted for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in remote communities found a higher rate of dementia than the NT study. This study also tried to include all people living in the community, rather than just those with medical records from using health services. The Kimberley study has shown that the dementia rate for remote living Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged 45 years and older is nearly five times higher at 12.4% when compared to 2.4% in the general Australian population[5].

The Koori Growing Old Well Study (KGOWS) worked with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in New South Wales and examined five sites across Sydney and the mid-north coast, using some similar measures of dementia to the Kimberley study, and a similar community-based approach. The KGOW study included a slightly older group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, aged 60 years and over. The study revealed dementia prevalence of 21% (age-adjusted) - three times the general Australian rate of 6.8%[6].

How does this compare to other populations?

It is important to know that dementia can affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at a younger age. During the ages of 45 - 69 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are affected by dementia much more than the non-Indigenous Australian population, but it is still not common to get dementia at this age. Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who get dementia are older than 60 years of age.

Also, whilst in the non-Indigenous population women are more likely to get dementia in old age, research has found Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are more often affected than females[3, 5].

Similar to the non-Indigenous population, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, followed by vascular dementia[1]. Factors associated with dementia include older age, little or no schooling, childhood trauma, unskilled jobs, smoking, stroke, epilepsy and serious head injuries, . People diagnosed with dementia are more likely to have poor mobility, incontinence, falls, depression and social isolation, as well as going to hospital more often and needing more care[5].

Dementia Research with Indigenous Populations around the World

As the number of people living until older age increases, more people will get dementia[7].

Dementia is not a natural part of ageing but getting dementia is much more likely to happen to people in later life.

There are types of dementia that impact people when they are much younger. These types of dementia are called Younger Onset Dementia, but most forms of dementia happen in later life (after the age of 65 years).

For Indigenous peoples, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and First Nations peoples, there are different rates of dementia in communities around the world.

In 2015, the University of Toronto did a review of all the existing studies they could find on Indigenous peoples and dementia and they found only 15 studies that were relevant to their criteria.

The research team reported that in the five countries represented in the studies (Canada, Australia, the USA, Guam, Brazil) dementia rates for Indigenous peoples ranged from 0.5% to 20%.

They also found that when studies did not assess cognitive functioning in a culturally appropriate way the rates of diagnoses were much lower in Indigenous groups.

This suggests that some studies missed people who had or were getting dementia in Indigenous populations by using a tool that did not suit Indigenous contexts.

First Nations people in Alberta Canada have an increased rate of dementia in their community when compared to the rest of the Alberta population. In this Alberta group, dementia seems to develop at a younger age in First Nations people than in the non-Indigenous population[8].

Overall it looks like there could be a higher rate of dementia for Indigenous people globally than for non-Indigenous populations.

But there are differences across different groups.

For example, in Brazil the Karaja people of the Amazon (who are quite an isolated group) had dementia rates that were lower than the rate of dementia for non-Indigenous Brazilians [9].

Lower rates of dementia in Indigenous populations have also been found in Cree and Cherokee populations in the US[10].

More work to understand dementia for Indigenous peoples needs to be done.